Although fine tuning LLMs can’t exactly be considered a new science, it carries a lot of nuances that many fail to recognize; and also carries over certain practices from traditional data science/machine learning. Kyle Corbitt, creator of OpenPipe, recently had a talk titled The Ten Commandments of Fine Tuning. In this blog post, I will list and explain these ten commandments while also providing further commentary of my own.

1. Do not fine tune

This will always be your default starting point. For any use case you might have, don’t fine tune. Start with prompting an already established model (GPT-4) first, always. For a number of reasons:

- Prompting offers faster iteration speed

- Better, smoother experience

- Can still be flexible (to a point) e.g.: dynamic few-shot examples using RAG

Generally, you would only fine-tune in case one or more of the following points are satisfied:

- You can’t hit your quality target

- Prompting can only take you so far.

- You can’t hit your latency target

- A smaller, specialized fine-tuned model can be faster than a prompted general purpose LLM.

- You can’t hit your cost target

- GPT-4 can be very powerful, but depending on your number of calls per day, it can be very expensive.

- Conversely, fine-tuning an LLM may require a sizable investment upfront, but you make your money back eventually.

2. Always start with a prompt

Even if we know beforehand that fine-tuning is necessary, owing to one or more of the above reasons; we should still start with prompting. For two reasons:

- Prompting gives us a nice baseline that we could work off of

- Whether it be quality, latency or cost; we need to know if we’re going in the right direction.

- Prompting is usually a good proxy to assess if the task at hand is possible at all or not

- If it (kinda) works with prompting, there’s a ~90% chance fine-tuning will make it better.

- If it doesn’t work with prompting, there’s only a ~20-25% chance it will work with fine-tuning.

- Generally, the more your task diverges from being a general purpose chatbot, the better it’ll do with fine-tuning.

The general playbook can be summarized as: 0–{GPT-4}–> 1–{Fine-tuned model}–> 100.

GPT-4 to prototype, fine-tune to scale.

3. Review your data

LLMs are as black box as they come, so always review every part of your data pipeline. You want to get a good sense of the distribution at hand, so you could make informed assumptions about what type of tests to write. Going a step further than that, always review your LLM results as well, log traces and query-response calls are crucial; tools like Langsmith and Braintrust are built specifically for that.

4. Use your data

Your LLM will inevitably do a bad job on some portion of the data, that’s the class of examples you should focus on. To actually determine what constitutes a “bad job”, critiquing can either be done manually by an expert or automatically by a LLM (LLM-as-a-judge). Once you’ve determined those examples, you would then figure out why the model isn’t doing well on them, and proceed to act accordingly in a number of ways:

- Manually relabel (using feedback from the expert)

- Fix the examples’ instructions (maybe even modify your prompt)

- “Heal” using a LLM

5. Some bad data is okay

This one is a bit contradicting and definitively controversial, so take it with a grain of salt. The whole idea is your dataset should be correct on average. Because you won’t ever always get perfect instructions in the wild, a few bad apples won’t hurt since LLMs are good at generalization anyway. In addition to that, 90% of the time your LLM will overfit when fine-tuning, so a bit of natural regularization is welcomed. It’s worth noting though that this does not work for small models, e.g.: tiny-llama.

6. Reserve a test set

Nothing new here, always reserve a test set. Your test shouldn’t exclusively consist of tough examples though, it should be random and representative of your training set.

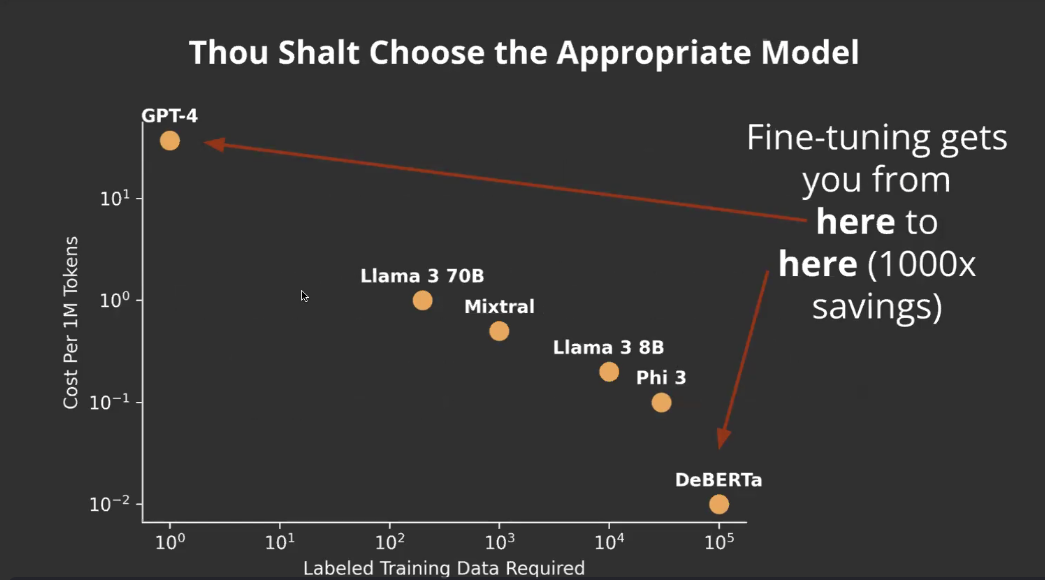

7. Choose an appropriate model

Fine-tuning is a tradeoff between the size of the dataset needed and model size (and performance); and subsequently, the eventual cost. Examine the above chart for example, it shows real life metrics for a specific task, performed across the listed models. In your particular use case the mileage may vary, but the general concept still holds. When prompting with GPT-4 you’ll need relatively no data, but it incurs the highest cost per tokens. As you decrease your model size, your training examples count grow, and inversely your cost decreases. For most cases, 7B/8B parameter models seem to be the sweet spot. In practice, you’ll find you can match GPT-4 performance for a specific task with 1-2K examples, but with significant cost reductions.

8. Write fast evals

Quality evaluations are probably the most crucial part of any ML system, LLMs are no exceptions. When fine-tuning, “vibe checks” are fine in the beginning, but you want to create a streamlined evaluation process to quickly evaluate performance and debug issues. Those fast evals are mainly separated into two parts:

- L1 evals

- These are unit tests and assertions, meant to be ran quickly against LLM responses for basic validity checks. These are your first line of defense.

- L2 evals

- These are further subdivided into human & model evals, meant to validate response quality.

- Human evals are provided by an expert (can be yourself).

- You can then document those human evals per response and use them to align a separate LLM to act as a critic for a more automated process (LLM-as-a-judge).

Components such as “critic” LLMs and “healer” LLMs are a meta-problem within your larger task, they should only be done using prompting and using the largest model you can afford.

9. Write slow evals

Slow evals are more concerned with the business outcome on a product level. LLMs can have good calls in isolation but can still interact badly with other parts of the system. Log traces can be useful in this case, but a more robust process of objectively measuring how well your system is doing is a must.

10. Don’t fire & forget

This is still a data science problem, so real world distribution shifts still exist. Constantly monitor your model’s prompts and responses and re-run your evals. This applies to your critic and healer LLMs as well, to get those as aligned as possible to your expert, they need random and periodic reiteration.

Bonus: Create, curate & filter your data

At some point in time you will be forced to synthetically generate data. In order to do that, you will have to reiterate on prompts for a while to get it right. But afterwards, the time invested in writing L1 and L2 evals will pay off:

- Use L1 evals to filter out invalid data

- Use L2 evals to filter out not good enough data

Lilac is one tool that is designed specifically for this.

Obviously, each use case is different, and not all of these rules will apply to your particular task. However, these guidelines will easily take you ~90% of the way.